Every decision to drink alcohol will be influenced, at least partly, by some form of marketing.

We are bombarded by high profile mass media advertising and marketing – from TV ads to billboards, sponsorship of a football team or celebrity endorsement. And point-of-sale promotions, price offers and low prices can trigger purchases that we didn’t set out intending to make, or encourage us to buy more than we planned.

But when it comes to young people, evidence is overwhelming that awareness of alcohol marketing is linked with starting to drink and drinking more.

We all like to think we’re immune from marketing. So why are tens of millions of pounds spent on it? The reason is because companies know that it presents their products and brands in the most attractive, memorable, and appealing way possible – ads are triggers to the eyes and ears for new and existing consumers. Just think about memorable alcohol marketing we have seen and potentially acted on, and catchphrases we may remember.

Alcohol industry documents show how their campaigns are carefully curated to tie alcohol to a sense of belonging, coolness, attractiveness, masculinity and femininity. The alcohol industry say their marketing doesn’t deliberately target young people. However –research with children from 13 onwards shows they talk favourably about alcohol marketing they have seen (opens pdf), are receptive to it and recognise the purpose is to drive consumption. It is, therefore, unsurprising that marketing is a key driver of their attitudes towards, and consumption of, alcohol.

The Youth Alcohol Policy Survey, a collaboration between the Cancer Policy Research Centre at Cancer Research UK and the Institute for Social Marketing and Health at the University of Stirling, provides a valuable monitor of where, and how often, adolescents recall seeing alcohol marketing. The results provide a stark reminder of why this continues to be an important issue.

In 2017, over 8/10 adolescents in the UK recalled seeing at least one form of alcohol marketing in the past month – and over half had seen 30 or more. Awareness was particularly high for alcohol adverts on television, celebrity endorsement, and special price offers. Almost a fifth of adolescents also reported owning branded merchandise like a sports shirt or branded drinks glasses.

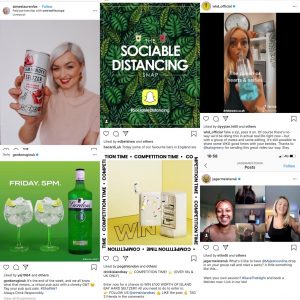

Emerging digital advertising also provides a new challenging marketing mix for young people to navigate, including adverts on YouTube, influencers on Instagram and fan pages on social media, all of which can be virally spread quickly and may be hard for young people or their parents to recognise as advertising.

It was exposed last year that three quarters of Australia’s top 70 Instagram personalities featured alcoholic drinks in their posts, but only a quarter had revealed they’d been paid to do so. We see similar examples in the UK of personalities who are followed by young people and teenagers promoting alcohol brands.

The Youth Alcohol Policy Survey shows just how successfully digital alcohol marketing is reaching and engaging adolescents. In 2017, around one-in-four of adolescents (opens PDF) recalled seeing adverts on alcohol on social media at least weekly, one-in-twenty (opens PDF) recalled seeing adverts on social media daily or almost daily, and a one-in-ten had participated with at least one form of alcohol marketing on social media in the past month (e.g. liking or sharing a post). New data from the 2019 wave, as yet unpublished, suggests that things haven’t changed.

It is now a decade since a 2010 Health Select Committee called for an overhaul in how alcohol marketing is self-regulated in the UK. This included recommendations for tighter controls that better protect young people and monitoring and enforcement processes to be independent of vested interests. There have since been similar calls from leading harm reduction agencies across the UK, in both 2013 (opens PDF) and in 2017 (opens PDF). To date, however, we have seen little actual change.

We are, however, starting to see some proactive steps elsewhere. For example, Ireland have begun to phase in a comprehensive suite of restrictions of marketing, while the Scottish Government plan to consult in 2021 on introducing new controls. Moreover, through their Childhood Obesity Strategy (opens PDF), the UK Government have shown some willingness to consider how commercial determinants influence food choices and dietary outcomes among young people.

I am sure many will watch the outcomes of these carefully and, if successful, they should provide a refreshed mandate to follow through on the recommendations made over a decade previously.

Dr Nathan Critchlow is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Social Marketing and Health, University of Stirling.